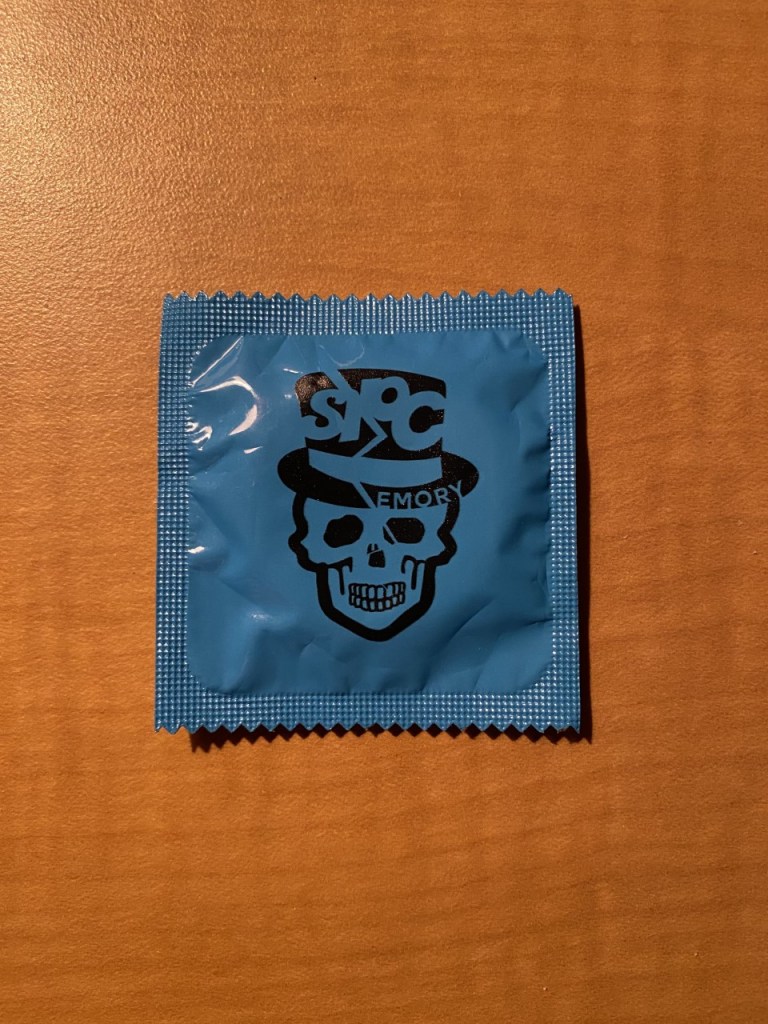

Emory University has a long and prestigious past; it also has a controversial one, especially in its early days. The research housed on this website reveals the evidence that ties Emory to a medical school culture, common throughout the United States and especially in the South, which facilitated the exploitation of marginalized bodies to the benefit of the students and the institution. Practices that caused the Georgia Anatomical Board to trade in black bodies and to apply a loose interpretation of the law which allowed for schools other than medical colleges to secure human remains as well as the Atlanta Medical College’s marketing of their access to dissection material to enhance their prestige, all shaped the course of medical education at the precursors to Emory Medical School, an institution which has never openly acknowledged that past. Further, from lynching postcards to dissection postcards and more, the environment of devaluing black bodies ubiquitous in the American South both reflected and enabled the creation of Dooley the Skeleton, Emory’s “unofficial” mascot. One can understand how medical students numbed by the dissection of black bodies and imbued in racist culture could map onto Dooley their perceptions of behavior that stereotyped blacks and reinforced their own feelings of white superiority. Dooley the Skeleton is a figure who emerged from a campus biology lab at a time when over 90% of human remains used in the school came from black bodies. He exited the lab and evolved into a character influenced by racist beliefs. Dooley may represent campus mischief, but he also reflects the history of cadaver theft, institutionalized racism in medical schools, and the exploitation of black bodies at Emory, its precursors, and the rest of the country. Looking at Dooley from the perspective of the history of dissection, his image as a racialized figure becomes clear and Emory University’s persistent use of Dooley in its marketing merits an open acknowledgement of this history.